The WSJ visits London: There Ngoes the neighbourhood

Parliament Square in happier times.

Parliament Square in happier times.

Wall Street Journal contributor Andy Ngo has caused quite a stir on social media with his bleak depiction of a recent visit to ‘Islamic England’. But is the criticism entirely fair? At first sight Ngo’s article seems merely hackneyed and cliché-ridden, but scratch the surface and there are layers of logical fallacy so deep that Jules Verne would have struggled to get to the bottom of them.

Legal disclaimer: The original text has been reproduced solely for the purpose of parody and ridicule, as will swiftly become apparent.

Other tourists may remember London for its spectacular sights and history, but I remember it for Islam. When I was visiting the U.K. as a teenager in 2006, I got lost in an East London market. There I saw a group of women wearing head-to-toe black cloaks. I froze, confused and intimidated by the faceless figures. It was my first encounter with the niqab, which covers everything but a woman’s eyes.

OK, dude. Stop right there. Are you seriously confused and intimidated by the sight of women going shopping? Because that’s what you’re describing. You’ve just forfeited the right to ever call anybody a snowflake ever again. Right, carry on.

This summer, I found myself heading back to the U.K. as it was plunging into a debate over Islamic dress. Boris Johnson, the country’s former foreign secretary and London’s ex-mayor, wrote a column opposing attempts to ban face-covering veils. Nonetheless, he added, “it is absolutely ridiculous that people should choose to go around looking like letter boxes.” The responses could hardly have been more heated.

Ah good, a quote from that nice fair-minded Boris Johnson to set the scene. For a minute there I was worried you might try to load the dice by citing a self-promoting serial liar who has spent several careers dressing up racism with bombast and hyperbole, and who once previewed a visit by Tony Blair to Africa thus: ‘The pangas will stop their hacking of human flesh, and the tribal warriors will all break out in watermelon smiles to see the big white chief touch down in his big white British taxpayer-funded bird.’ Panic over, we can continue on our way.

I wanted to cut past the polemics (you can’t wash out the stain of Boris that easily, my friend, as wiser heads will testify) and experience London’s Muslim communities for myself. My first visit was to Tower Hamlets, an East London borough that is about 38% Muslim, among the highest in the U.K. As I walked down Whitechapel Road, the adhan, or call to prayer, echoed through the neighborhood. Muslims walked in one direction for jumu’ah, Friday prayer, while non-Muslims went the opposite way. Each group kept its distance and avoided eye contact with the other. Mate, you’re in London. Nobody ever makes eye contact, not even with close family members during a life-threatening emergency. A sign was posted on a pole: “Alcohol restricted zone.” So the first concrete evidence of the deadening impact of Islam on British cultural life is a council notice prohibiting public drinking. What a happy place Whitechapel Road must have been in the good old days, before the Muslims snatched away people’s right to wander around plastered in the daytime.

Women and girls were dressed in hijabs, niqabs and abayas (robes). Some of the males wore skullcaps and thawbs, Arabic tunics, with their trousers tailored just above the ankles as per Muhammad’s example. The scene could have been lifted out of Riyadh, a testament to the Arabization of Britain’s South Asian Muslims. Since trousers themselves are an Eastern invention, I can only presume our writer stayed faithful to his origins by sporting breeches and a codpiece. At the barbershop, women waited outside under the hot sun while their sons and husbands were groomed. Ah, yes, the sinister Muslim practice of standing outdoors in the sunshine. What barbarities will they impose on us next?

Inside the East London Mosque, visitors were expected to dress “modestly.” Headscarves were provided at reception for any woman who showed up without one. Wait a minute, are these Muslims handing out free clothes so people of other faiths can visit their place of worship the same ones who refuse point-blank to have any contact with outsiders? I’m struggling to keep up. A kind man (a kind ‘man’, you note. Not a kind Muslim. He must be there on work experience) on staff showed me around the men’s quarters. He gave me a bag filled with booklets about Islam. It’s easy to see why Ngo feels intimidated by these people. In one, Muslims are encouraged to “re-establish the Shari’ah,” or Islamic law. Those who ignore this mandate are “of little worth to any society.” So Muslim religious leaders hand out books telling people to submit to God’s law. Radical stuff. Imagine the fuss if the WSJ ever finds out what Christians get up to in those big stone buildings.

That night, I visited the Houses of Parliament. Rifle-carrying police officers greeted me when I stepped out of the Tube. The extra security was mobilized in response to last year’s car and stabbing attack in Westminster by Khalid Masood, who killed five people. Yes, Londoners must pine for the simpler days when all they had to worry about was being blown up by an IRA car bomb. Outside the station, there are roadblocks along Westminster Bridge and a new security fence in front of the palace yard. I asked an officer about Masood’s attack. “I’d rather not talk about it,” he replied. “I was there that day.” What sort of a society have we become when we’re too cowed even to share our private traumas with nosey strangers?

Forty-eight hours later, I woke up to the news that a car had rammed a Westminster security barrier. Police arrested Salih Khater, a 29-year-old Sudanese refugee who had been given asylum and British citizenship. Three people were injured in the attack. London’s mayor, Sadiq Khan, expressed support for banning vehicles from parts of Parliament Square. It’s a devastating picture of a country being hollowed out by multiculturalism: a few more of these attacks and we’ll have to seriously think about banning vehicles from the whole of Parliament Square.

Next I visited Leyton, another district in East London where some Muslim social norms prevail. An Arab cafe near the Tube station was filled with men; no women were inside. I’m always sickened to hear of these backward cultures that won’t let women use their leisure facilities; in fact, I was fulminating against it just the other night down at the golf club. An Islamic bookstore sold hijab-wearing dolls for children. The dolls had blank, featureless faces, since human depictions are prohibited in conservative Islam. But perhaps one day they’ll cast off the shackles of conservative Islam and embrace more enlightened images of womanhood such as Barbie.

I stopped outside the Masjid al-Tawhid, a South Asian Salafi mosque and madrassa (school), just before afternoon prayer time. A group of girls in robes and veils walked around back, toward the dumpsters, where the women’s entrance is located. I later saw the Islamic Shari’a Council of Leyton. This community has religious, educational, business and legal institutions to maintain a separate identity. And the worst thing is that when they’re not educating children, providing legal services, giving pastoral support and running commercial enterprises they just lie around waiting for the benefit cheque to arrive.

All this gave me pause. But I was unprepared for what I would see next in Luton, a small town 30 miles north of London and the birthplace of the English Defense League, which has held unruly anti-Muslim demonstrations. That’s an understatement on a par with saying General Pinochet had a bit of a cavalier attitude to airplane safety. At the Central Mosque, I met a friendly group of Punjabi-speaking young men. “You’ve come to see Luton?” one struggled to ask me in English. I don’t know: it seems pretty grammatically sound to me, and I can be extremely pedantic about these things. The young men asked me to follow them through the town center. Polite young men offering tours of the locality! Next you’ll be telling me they brought out the comfy chair. Perhaps they should have staged an unruly demonstration to make their esteemed visitor feel more welcome.

Within minutes, we walked by three other mosques, which were vibrant and filled with young men coming and going. We passed a church, which was closed and decrepit, with a window that had been vandalized with eggs. The true state of Luton’s 117 churches (rather than its 26 mosques) has already been elucidated by more knowledgeable commentators than me. Let’s pause instead to marvel at the trained observer who can’t work out why the mosques should be livelier than the churches on a Friday afternoon. We squeezed by hundreds of residents busy preparing for the Eid al-Adha holiday. Sorry, make that on a Friday afternoon IN THE MIDDLE OF A MUSLIM HOLIDAY. Girls in hijabs gathered around tables to paint henna designs on their hands. All the businesses had a religious flair: The eateries were halal, the fitness center was sex-segregated, and the boutiques displayed “modest” outfits on mannequins. Come back to the UK in December, buddy, the omnipresent religious iconography will blow your socks off. Pakistani flags flew high and proud. I never saw a Union Jack.

The men finally led me to a discreet building that housed a small Islamic center. They spoke privately to its imam. I was led upstairs to see him. The imam asked me if I was prepared to convert. Apparently there had been some miscommunication with the young men. I told the imam I wasn’t ready for that, but I would appreciate any literature I could take home. He led me to a bookshelf and said I could have whatever I wanted. I grabbed the first booklet that was in English. It was by Zakir Naik, a fundamentalist preacher from India. Our intrepid hero goes to an Islamic study centre. He meets an imam. The imam offers him some books. The books turn out to be about Islam. As plot twists go, this is right up there with the finale of Twin Peaks. “The Qur’an says that Hijab has been prescribed for the women,” the booklet explained in one section, “so that they are recognised as modest women and this will also prevent them from being molested.” After digesting that incendiary text, we can only hope Mr Ngo sought comfort in the words of Deuteronomy: ‘If a damsel that is a virgin be betrothed unto an husband, and a man find her in the city, and lie with her; Then ye shall bring them both out unto the gate of that city, and ye shall stone them with stones that they die; the damsel, because she cried not, being in the city.’

Other tourists might remember London for Buckingham Palace, Piccadilly Circus and Big Ben. I’ll remember it for its failed multiculturalism. Or perhaps this is what successful multiculturalism looks like. Let’s examine the clues: Friendly young men giving free tours of the neighbourhood. Street festivals. Girls painting their nails. Schools. Community centres. Successful local businesses. Fitness centres. Bans on public drinking. And not an unruly demonstration in sight. Who would want to live in a place like this?

Let’s ditch the sexist myth of the hapless male

Here’s a list of Father’s Day presents, culled at random from the internet: drones, ties, DIY tools, thermos flasks, ties, home brew sets, wireless speakers. All of them, to a greater or lesser extent, underline the image of the man of the house as someone whose natural environment is outside the house, whether it’s in the office, down the pub, in the tool shed or halfway up a mountain with a hip flask for company. While Mother’s Day is all about celebrating the hard work that mothers do to keeping their children fed, clean and emotionally nourished, the tone of Father’s Day is a mix of gratitude and astonishment that fathers spend time at home at all.

Here’s a list of Father’s Day presents, culled at random from the internet: drones, ties, DIY tools, thermos flasks, ties, home brew sets, wireless speakers. All of them, to a greater or lesser extent, underline the image of the man of the house as someone whose natural environment is outside the house, whether it’s in the office, down the pub, in the tool shed or halfway up a mountain with a hip flask for company. While Mother’s Day is all about celebrating the hard work that mothers do to keeping their children fed, clean and emotionally nourished, the tone of Father’s Day is a mix of gratitude and astonishment that fathers spend time at home at all.

The hapless male – self-obsessed, barely able to make a cup of tea unsupervised, with the attention span of a gnat and a monochrome emotional range that alternates between apoplexy and lassitude, and above all totally oblivious to the work women do to keep him afloat – has become a trope of modern culture. Women keep the world turning while men take the credit for it. There is an element of truth to it: when my wife died, four years ago, it was a revelation to discover how much time and effort went in to running a household, and how much we undervalue it. I’d kidded myself, like many a self-styled progressive man, that we shared the domestic duties equally, only to find that my workload as a single parent was three or four times greater. But the experience also taught me that the implicit assumption that men are inherently less capable of running households or raising families is dishonest, sexist and wrong.

It’s sexist not because it’s degrading towards men – though the surprised expressions that greet the shock disclosure that I fold my own bed linen can get tiresome – but because it perpetuates the notion that cooking, cleaning and raising children is the woman’s natural domain. Fathers in the playground tend to be asked if they’re ‘looking after the children’, with the implication that they’ll hand them back to the real parent at the end of the day. What surprised me more was the extent to which women buy into this myth, because gendered roles are so ingrained in our social fabric that many women find validation primarily in how well they fulfil the role of wife and mother (two words that appear in social media profiles far more frequently than ‘husband and father’) rather than what they achieve in their careers or their personal lives.

I won’t deny for a minute that women are disadvantaged and imposed upon by this settlement to a far greater degree, both in terms of their career opportunities and perceived value to society. If children are starved of attention because both parents are working all day, it is the mother who is deemed to be at fault. Conversely, credit is quickly bestowed on men who carry out what for women are routine tasks. A man who takes half a day off a week to spend time with his children is lauded as a champion of equality, while his partner who reschedules the other four days around the school timetable is perceived to be slacking off early. The consequence is that the bar for male domestic achievement is set far too low. Dads are lavished with praise for performing the simplest of chores, such as changing a nappy or loading the dishwasher, and when they fail the response of their partner is often to roll her eyes, give a heavy sigh and take over. All of which reinforces the perception that men are genetically unsuited to the homemaker’s role. It gives them a free pass to be lazy and irresponsible, because raising children isn’t really their job anyway. Until eventually they give up, or relegate it to the status of an occasional hobby, leaving their partners to pick up the slack and their children deprived of a strong relationship. Even in professional circles, the assumption prevails that the mother will become the primary carer after a separation because fathers are unreliable. Men in my situation, who are forced by circumstance to become mother and father, often have to wade through a thicket of prejudices about their ability to adopt to their new role: one acquaintance advised me to pick up ‘tips and tricks’ from the mothers at my children’s school, the implication being that I was starting from scratch.

Thankfully, we have moved beyond the days when men went straight from being looked after by their mothers to being looked after by their wives, leaving them stricken by widowhood. Yet the hapless male is a close cousin of the helpless male, who panics and flees in the face of an emotionally charged situation. We should stop trivialising inequality on the home front or pretend that it is tangential to the main issue. Asking men to step up and take on their share of the domestic burden, and refusing to accept ‘he can’t’ for an answer, is liberating for both genders, because it encourages proper respect for both the work and the person who performs it.

My first publication year

2018 is going to be publication year. I ought to be excited. I should probably be ecstatic. For around a decade ‘have something published’ headed my list of new year’s resolutions with the grinding recurrence of a Cliff Richard Christmas single. And now it’s actually happening, and my primary feeling is apprehension.

2018 is going to be publication year. I ought to be excited. I should probably be ecstatic. For around a decade ‘have something published’ headed my list of new year’s resolutions with the grinding recurrence of a Cliff Richard Christmas single. And now it’s actually happening, and my primary feeling is apprehension.

At the risk of stating the obvious, having books published is the main thing that distinguishes writers from non-writers. Hang about with writers and it starts to seem like the most normal thing in the world – it’s what everyone does for a living, after all. But to non-writers, having a book out is an exotic event shrouded in mystique, to be discussed in excited whispers. (Where will you have the launch? Who will you invite? Will there be free drink?) Bookshops are full of books by famous and obscure authors, yet many people go through their lives without ever meeting one. It sometimes seems as if readers and writers inhabit parallel universes.

Plug coming up

So 2018 will be the year in which I cross that divide from faithless reader to apprehensive writer. It’s something I’ve aspired to for the majority of my 43 and a quarter years, so why do I feel so ambivalent about it? Partly it’s a reflection of circumstance. In all those years that I resolved to enter the ranks of published authors, I never imagined that my wife would be dead before I achieved that ambition – still less that her death would be the catalyst. There was a time when I would have given anything to see my name on the spine of a published book. Now that moment has arrived it feels like a hollow victory, because if the choice were available I would have traded inany amount of book sales to stave off Magteld’s demise. At the same time, I’m not an accomplished enough liar to pretend that I don’t want to see copies leap, fly and skip off the shelves when All The Time We Thought We Had is published on September 6 by Birlinn (ICYMI, that was the plug).

Hence the ambivalence, but that’s not the only source of apprehension. I wrote the book as a tribute to Magteld, but what if it lacks the essence of the woman who lit up my life for 20 years? I worry nobody will read it and it will become an empty monument to my own vanity; I worry too many people will read it and I’ll no longer be able to fetch milk and butter from the supermarket unmolested. I worry people will buy it but not read it, or read it but not understand it, or understand it but not appreciate it. I’d contend I’ve become less ambitious since Magteld died. In particular I find the flaky notion of a “career” an increasingly absurd measure by which to define a human lifespan. And yet here I am, still secretly desiring a career as a writer and yearning for recognition and material success, despite being old enough to know better. Everybody believes they have a brilliant book in them, but once it’s out of you the only true test is how well it fends for itself in the outside world. Books are like children in that regard: you nurture them, fuss over them, agonise about their future and invest all your energies in giving them the best possible start, but there comes a day when you have to let them go and hope they’ll be successful enough to look after you when the days start to shorten.

The Weinstein spectrum

Since the protective cocoon around Harvey Weinstein started to crumble a few weeks ago I’ve been following the #metoo hashtag on Twitter with mixed emotions. Specifically a blend of horror, shock, disgust, bewilderment, helplessness and dismay. Some people have berated men for our deafening collective silence on the issue, but I’d argue that this is an excellent opportunity to pipe down for a minute and listen. I don’t have anything clever, funny or enlightening to say on the subject of sexual harassment, just a sense of pallid unease as the warning lights become a shimmering red mass. Besides, anyone who supposes that the discussion will be enriched by the inclusion of more male voices clearly hasn’t spent much time on Twitter.

So what can men do about it? Few of us can see a wonky table leg without attempting to prop it up with random bits of wood and card, so we would feel better if there were a quick remedy to hand. There are a few. For starters, we can stop wheeling out the ‘not all men’ argument. If all women have been subjected to this, it’s logical to conclude that all men are culpable to some degree. And not just in the sense of turning a deaf ear to the boss’s sexist jokes or the loudmouth on the bus. We are all somewhere on what David Aaronovitch this week called the Weinstein spectrum. Perhaps it was inadvertent. Perhaps you were young, or drunk, or feeling lonely and unloved. Perhaps you didn’t know where to look on a crowded train until a pair of breasts caught your gaze. (I’m sorry, I’ll rewrite that. Perhaps you didn’t know where to look until somebody’s breasts caught your gaze. The breasts weren’t hovering in the air by themselves: they were part of a person who hadn’t asked to be gawped at by a lascivious stranger). Perhaps you thought someone was turning you down because she was worried about being disappointed, and you just needed to reassure her you could show her a good time, when actually she was worried about being assaulted and your reassurances were nothing of the kind. It doesn’t matter. You were still being a jerk. Acknowledge it and try to do better. And I’d love to deploy the other favourite excuse, that my intentions were honourable, but that’s not true either. Sometimes I was over-attentive towards someone, even in ostensibly nice ways, because I wanted to have sex with them. You can argue that that’s not a bad thing necessarily, just as you can argue that lots of charities benefited from the machinations Jimmy Savile contrived to get the keys to Stoke Mandeville Hospital, but if your motives are dishonest there’s only one person to blame when they lead you into trouble. (No, it’s not the woman. Go back and read it again.)

But in general there’s no DIY fix to the pervasive culture of harassment. Even the best attempts to devise a counter-hashtag have been cosmetic and unconvincing. Proclaiming you will behave better from now on at least shows self-awareness, but it’s a bit like promising to start going to the gym in January. Are you sure about speaking out when the boss starts up the sexist banter in a room full of sycophantic middle managers? Will you still do it when there are no women present, because you recognise that passive participation in what people who’ve never played professional sport call ‘locker-room talk’ is endorsing the unacceptable? How will you really respond when a man who’s got millions to invest in your company tells you after a few drinks that he likes to grab ’em by the pussy?

I’m not comfortable either with the idea of public confession. In the first place, it encourages relativisation, because I can say hand on heart that I’ve never been as appalling as Savile, or Harvey Weinstein, or this guy, so where’s the problem? As any Catholic will tell you, once you’ve confided your sins and said the requisite Hail Marys, it’s easy to lapse into the belief that you’ve discharged your responsibility. There’s also the risk that the victim recognises the scenario and is confronted with something they may have tried very hard to forget. And there’s the danger generic to all amnesties: how do we know that the person who admits to pestering a woman in a bar isn’t trying to deflect attention from something more brutal and unspeakable?

Sex is complicated. It’s playful and devious, it relies on illusion and suggestion, metalanguage, blurred lines and ambiguous gestures. It fits uncomfortably in the constraints of civilised society. But as with all forms of play, it depends on consent and mutual respect. If someone doesn’t want to join in your game, leave them alone. No means no, always, even when it’s phrased as ‘not yet’ or ‘some other time’. Sex isn’t a reward for virtue or wealth or status, or giving someone a pay rise, buying them a nice meal or escorting them home from the pub. And sexual disappointment is no different from any other type of disappointment. Women who don’t fancy you aren’t ‘putting you in the friendzone’: they’re offering to overlook your clumsy sexual presumptiveness and let you show you’re a decent person beneath all that posturing.

Finally, you may have your own #metoo story, of a time when you were on the receiving end of some unwanted attention. (I know I have.) If so, save it for another time, or reflect on the fact that what was an isolated incident for you is part of the everyday fabric of many women’s lives. The things men can do to respond to #metoo are smaller and simpler. We can examine ourselves. We can keep listening. We can keep reading. And we can keep quiet until we’ve got something worthwhile to say. Silence is nothing to be ashamed of.

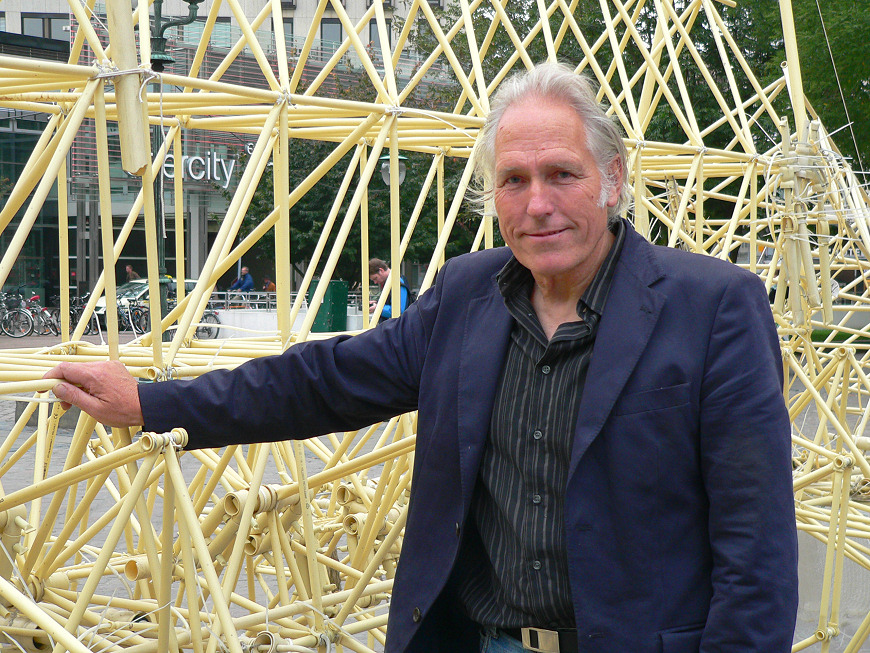

Evolution and the Strandbeest

Photo by Axel Hindemith via Wikipedia, September 2007

Theo Jansen, whose work I was lucky enough to see taking a stroll on The Hague’s south beach this afternoon, has an interesting theory about the evolution of his Strandbeesten. The sight of Jansen striding up the beach, dragging his whirling plastic contraption and a swarm of curious onlookers with him, put me in mind of a Victorian showman advertising his circus. Jansen has made the wind-propelled creatures, constructed from PVC tubes and joints, his life’s work, but doesn’t intend to stop there. His ultimate ambition, he told an audience on the sands, is to distil his designs into a single creature that is wholly self-reliant and can live on after his death.

At what point can we deem a man-made creature to be alive, or even independent? Jansen’s creations are beautiful and graceful, but a long way short of intelligent. They can only move with the explicit intrusion of their creator, who points them in the right direction, loosens their sails and decides when they should stop. More sophisticated versions use compressed air or store wind in plastic bottles so they can walk in the absence of wind. And, of course, they cannot think, feed, or reproduce. But the last point brings us to Jansen’s theory.

He drew his audience’s attention to a symmetrical pair of Strandbeesten he called ‘the proboscis’. Instead of walking, the creatures have pointed noses that dance and sway in harmony, like interlocking waves. It is a hypnotic sight, but Jansen struggled at first to understand what purpose this movement could have. Perhaps, he mused, they were trying to seduce each other, but that would be useless, since Strandbeesten cannot physically multiply. But then he realised that the Strandbeesten were seducing not themselves, but other creatures. Specifically students, who followed the instructions on Jansen’s website to bring their own Strandbeesten into being.

An unexpected implication of Jansen’s discovery is that the Strandbeest is a parasitic organism. It lodges itself in the imagination of its human hosts and inspires them to create its offspring. We could call it an intellectual parasite. This also gives the Strandbeesten a good chance of evolving further, since no two people will build the creatures in exactly the same way, and multiple creators will have more opportunities to improve the design. As so often, what appears at first to be a frivolous embellishment turns out to be vital to the survival of the species. The danger, Jansen warned his audience, is that we humans will become so infatuated with the Strandbeesten that they take over our lives. This we must resist.

Announcement

Photo (c) Traci White

I’m delighted to announce that my memoir, All The Time We Thought We Had, will be published by Birlinn, provisionally in the spring of 2018. What’s it about? In the first place it’s the story of how Magteld died of breast cancer in 2014, within two years of first being diagnosed. It’s about how our family emigrated while caring for a dying woman. It’s about how my two autistic children adjusted to living in a new country in the absence of their mother, and how we tackled all these challenges as a family lashed together in grief. Most of all it’s about love and loss, fate and hope, fragility and strength, new beginnings and unexpected journeys, and how our memories shape our future.

I also have a Facebook page which you’re warmly invited to follow. I’ll try to post interesting stuff in amongst the flagrant self-promotion, but no promises.

Obligatory pensive author shot by the excellent Traci White (Groningen, not Montana) – please contact her if you want to use it for any reason.

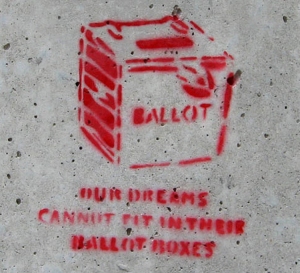

After 2016, whither democracy?

At the end of a year dominated by the politics of fear and division, a few bold individuals resolved to speak up for the values of solidarity and compassion. Here are the words of one of them: “Even with the inspiration of others, it’s understandable that we sometimes think the world’s problems are so big that we can do little to help. On our own, we cannot end wars or wipe out injustice, but the cumulative impact of thousands of small acts of goodness can be bigger than we imagine.”

At the end of a year dominated by the politics of fear and division, a few bold individuals resolved to speak up for the values of solidarity and compassion. Here are the words of one of them: “Even with the inspiration of others, it’s understandable that we sometimes think the world’s problems are so big that we can do little to help. On our own, we cannot end wars or wipe out injustice, but the cumulative impact of thousands of small acts of goodness can be bigger than we imagine.”

In her Christmas Day message, Queen Elizabeth gave the gentlest of warnings about letting a sense of helplessness set in and calcify the social fabric. The sentiment was expressed more pointedly on the same day by a member of the same exclusive club, the Dutch king Willem-Alexander:“The extreme seems to have become the new normal. In their search for security, groups become entrenched in their own convictions. Open conversations often become impossible. Many of us have the sense that we live in a country where nobody listens.”

Historically democracy evolved to protect society from despotic monarchs wielding their power excessively. This year may well be remembered as the moment when that process turned on its head. While democracy delivered us Brexit and President Trump, unelected monarchs became the last hope for the values which elected leaders have been trampling all over. In September King Harold of Norway proclaimed his nation’s diversity in a short but fiery speech that resonated around the world: “Norwegians are enthusiastic young people – and wise old people. Norwegians are single, divorced, families with children, and old married couples. Norwegians are girls who love girls, boys who love boys, and girls and boys who love each other. Norwegians believe in God, Allah, the Universe and nothing … My greatest hope for Norway is that we will be able to take care of one another.” Contrast this with the splenetic outbursts of Trump, who has vowed to build walls with one country, denounced climate change as subterfuge on the part of another, proposed banning millions of Muslims from his borders and plans to weaken the authority of Nato. From Victor Orban in Hungary to Putin, Erdogan and Trump, the threat to democracy in modern times comes not from foreign despots, but from demagogues dismantling the system from within.

‘Democratic deconsolidation’

In their research on ‘democratic deconsolidation’, Yascha Mounk and Roberto Stefan Foa identify an alarming contrast between generations: among Americans born in the 1930s, 75% believe it is ‘essential’ to live in a democracy, but for those born in the 1980s, the figure is closer to 25%. Trust is eroding, not just in elected politicians, but in democracy itself. As society fragments, people’s confidence in the political order to secure their freedom, health and prosperity diminishes. They resent the system they are asked to participate in and make decisions that highlight its weakness. Trump won by dragging down expectations so low, and destroying any pretence of standing up for democratic values, that he became an impermeable, scandal-proof candidate, immune from the constraint of being held to account for his words.

Since the Renaissance it has been an article of faith that democratic decisions are better decisions. In 2016 we learned that this is a fragile illusion. The value of democracy is contingent on the goodwill of the electorate. Brexit was a democratic decision foisted on a government that had (and still has) little idea of how to carry it out, by a people who had little regard for the consequences. The Dutch prime minister, Mark Rutte, has spent most of the year dealing with the fall-out from a referendum in which voters demanded that he withdraw his signature from an accession treaty between the EU and Ukraine, without the faintest interest in the treaty’s aims or the effect of withdrawing on the Netherlands’ foreign relations. They simply wanted him to voice their disaffection with the world order.

In 2008 Barack Obama was elected president with a message of hope. He was by no means the first. But voters who have seen increasingly little material improvement in their lives have lost patience with politicians who have spent the last 40 years stripping themselves of power and endorsing the tyranny of the free market. America in 2016 is a land of lost hope, where the hopeless have taken revenge by electing the most hopeless leader imaginable. The hope is now invested, perversely, in popes and potentates. Queen Elizabeth’s call for “thousands of small acts of goodness” is a reminder that such acts are still possible and necessary in a fragmented society. And Willem-Alexander’s Christmas address included an appeal to people to resist the destructive forces of populist nostalgia: ‘This is how we want to live here, as free and equal people … As the world around us offers us less stability, we need to hold on to what we share and protect the things that unite us.’ When hereditary rulers have to defend the foundations of democracy against elected leaders, it a sign that democracy is in very serious trouble indeed.

Loneliness: the secret circle of hell

Picture: The lonely runner, by Nick Kenrick on Flickr

“We cannot cope alone,” wrote George Monbiot in his essay on the age of loneliness, published in The Guardian two years ago. Human beings are social animals: we crave the support, approval and love of like-minded individuals. But society in the last 50 years has become steadily more atomised, with a relentless focus on individual success. The Olympics have been reduced to the singularity of winning – silver medallists cry tears of rage and act as if a close relative has died, just because one person out of thousands performed slightly better than them at an arbitrary task. We commiserate with losers rather than celebrate their contribution to the spectacle. There is no solidarity with, or appreciation for, a worthy adversary. And so it is in society: performance is paramount, failure is shameful and social status depends on meeting somebody else’s measure of success, rather than the intrinsic worth of your endeavours.

The greatest failure, the biggest shame of all, is to be lonely. Stress, depression, anxiety, burnout: all these are recognised conditions nowadays and good therapeutic treatments have emerged to help people cope with them. But loneliness? Get a grip. What do you want, a prescription to take down to Aldi so you can stock up on white wine and multipacks? Lonely people are losers, sad sacks, easy prey for spurious dating websites and cowboy builders, and they only have themselves to blame. Who can fail to have a social life in a world where we are constantly being nagged to connect? We can strike up friendships with strangers on the other side of the world, have Twitter chats with our favourite celebrities and find partners online (we can even vet their social media profiles before the first date). We follow our friends on their holidays, cheer their achievements on Facebook and read their blogs. And yet many of us are lonely – profoundly lonely. We don’t want to admit it, because we are under pressure to project idealised versions of ourselves. Social media amplifies this: we are on permanent display. We must be sharp, witty, insightful, passionate and provocative, keep pace with the latest news, surf the waves of outrage and wish everybody a happy birthday.

Often we don’t see loneliness because it is camouflaged in the jungle of self-promotion that is social media. Recently a young woman called Louise Delage exploded onto Instagram as she toured Europe’s party capitals, seemingly having the time of her life, leaving a trail of selfies emblazoned with happy hashtags in her wake. After two months, during which she had accumulated 16,000 followers, came the sting: ‘Louise’ had been created by an advertising agency for an addiction awareness campaign. Few of those who had been sucked into her lifestyle noticed that she had a drink in her hand in every shot, a tell-tale sign of alcoholism. But even when the secret was out, hardly anybody remarked on the other common thread running through the pictures: in the vast majority of them, as she cradles her half-empty glass, Louise is alone.

Since being widowed two years ago I have struggled to get out of the house. I am occupied with my two children from 7am until 10pm, I can’t commit to any kind of regular social activity, like joining a sports club, and dating is off-limits for both emotional and logistical reasons. If I massage my schedule I can squeeze in a Skype call with an old friend (being a recent immigrant makes it extra challenging). The theatre, the cinema, the concert hall, festivals, restaurants, even the shops (apart from the local supermarket) exist in a parallel dimension. There is occasional respite when the children’s grandparents come and look after them every few months. But it is hard to nourish and sustain friendships on such meagre rations of time, and impossible to strike up new ones, in a new country where I have a permanent deficit in terms of language, culture and social networks.

The depth of my social ostracism only hit home the other week when I went for lunch with a friend – not even a close friend, but somebody who’d been very generous with their time over the last two years, offered a listening ear and given some friendly advice. When I got home I was afflicted by a horrible sense of emptiness, a bitter mixture of anxiety, loss and regret. In the next few days I twice went out shopping without my wallet, locked myself out of the house and neglected to pack the mid-morning snack in one of my children’s school bags. Any of these incidents on its own I would have dismissed as a minor lapse of concentration, but taken together they were evidence of a looming crisis. I spent the week moping, exhausted and irritable. On looking back it dawned on me that that lunch date in mid-September was only the second time this year that I’d sat down to eat with another adult who wasn’t related to my children.

‘I have binged on solitude like a seasoned drinker who discovers in his mid-fifties that he has type 2 diabetes’

It was a shock to realise how hard I found it to be alone, because growing up as an only child taught me to appreciate my own company. My mother complimented me on my ability to entertain myself, which may not have been entirely altruistic. But there is difference between solitude and loneliness. Being alone once in a while, in the context of a stimulating social life, can be refreshing and vital, an opportunity to step off the treadmill and let your mind breathe. A day spent alone at the end of a busy week is as relaxing as a glass of wine, and combining the two is possibly the best relief of all. But prolonged periods of isolation corrode the soul. I thought, having spent regular spells by myself, that I was immune to the disease of loneliness. But I have binged on solitude for too long, like the seasoned drinker who champions his ability to turn up to work the morning after a heavy session, year after year, only to be shocked in his mid-fifties by the discovery that he has developed type 2 diabetes.

Loneliness is a dim fetid corridor that deafens you with the echo of your own footsteps. Profound loneliness feels like walking around inside a plastic bubble. The difficult times aren’t when you are away from people, but when you are among them and it feels as if life is going on around you but separate from you. Sometimes people come up close to the bubble; sometimes they even press their faces right into it and see you, but there is no real connection beyond than the formal interactions of shop assistants requesting and receiving money, or neighbours stopping for a 30-second chat before heading off to a proper social engagement. Their fingers prod the bubble but they cannot step inside it and you see, but do not feel, their prodding attempts at contact. And another potential connection fizzles and dies.

I know what you’re thinking: there are worse diseases out there than feeling a bit isolated. But loneliness is physically as well as mentally inhibiting. In a study that followed 2000 people aged over 50 conducted over six years, those who reported being lonely had a 14% higher risk of dying. That was twice the risk for obesity. The Lonely Society, a report by the Mental Health Foundation published in 2010, said the “individualistic society” was responsible both for increased loneliness and an increase in common mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety over the last 50 years. John Carpioccio, a social neuroscientist at the University of Chicago, has gathered scientific evidence of the physiological impact of loneliness: stress hormones, a weakened immune system and lower cardiovascular function, equivalent to the damage done by smoking.

The perniciousness of loneliness is a downward spiral. You don’t bother your friends with it because you don’t want to be bad company. You feel everybody else is doing OK, they’ve got their own worries to deal with and you just need to get over yourself. If you do raise the subject, most people prefer to give superficial advice, such as taking up a new hobby, rather than getting into a situation that can be confusing, tiring and energy-sapping. And if you do find that rare person who can understands, you are terrified of leaning on them too hard and alienating them. In the end you are left with nowhere to go but inwards, into the secret circle of hell, the cold cell in the hive, that is your own diminished company.

Whether loneliness is an epidemic is a matter for the experts. Certainly it is a pervasive condition. The permanent fog of anger on Twitter, notably, gives voice to a widely-felt sense of disappointment and disaffectation. It is tied with low empathy – angry Tweeters scramble to judge anyone who makes a mistake or shows a personal weakness, and compete to see who can ascribe the most malicious motives to a simple misjudgment. They wallow in paranoia, feel quickly threatened and revel in the misfortunes of others. These are all characteristics of lonely people. But how do you fix people who are so entrenched in their unhappiness that they shun all efforts to help them?

There seems to be a tipping point with loneliness where it becomes a one-way plunge into the abyss. I have seen elderly relatives, weakened by grief, gradually withdraw from society in a ghastly pas-de-deux, as their social skills fade and those who were once close to them feel their compassion ebb and drift away. Somehow I have to keep on, for the sake of my children, and try not to think about what happens when they leave home. I don’t fear death so much as the emptiness in between. So I don’t want to succumb to loneliness or stay silent about it. I want to fight it the way other people fight cancer. I want my part in the drama of life to be acknowledged. I’ve always got by with a small social circle and thought I would be strong enough to manage on my own, but the past two years have forced me to accept that George Monbiot is right: we cannot cope alone. Without connections we wither.

Chippings from the quarry #4: Stood up

It seems ridiculous now, but there was a time when every date you went on carried the risk of the other person not showing up. In other words, you’d be stood up. Nowadays when your date doesn’t appear you summon your pocket djinn, dispatch a message demanding to know where the hell they are, and it flies to their phone like a cupid’s arrow dipped in poison. Either they have a good excuse, like they’ve just pulled over by the side of the road to administer the kiss of life to an accident victim, or they have to lie nimbly, or admit to being an inadequate person. Either way, you don’t leave before you’ve had an explanation, and in many ways this feels like progress.

A tangled ivy of etiquette grew up around the unsavoury business of being stood up. The main scruple was how long you should wait before you abandoned hope and shuffled off. You would fidget, push the empty glassware round the table as if re-enacting a battle scene, check your watch too often and try to dodge the barman’s doom-laden gaze. Your second concern was to salvage your dignity as you left, alone, humiliated and betrayed by someone who had fallen so fast in your affections that they left scorch marks on your soul. They didn’t even have the basic decency to be there to absorb your wrath.

Sometimes you stayed in the bar and took a drink to console yourself, and while you were drowning your despair someone else came and sat with you, and you were so grateful for their company and their laughter and the way they swept away your disappointment that you ended up going home with them instead, and by the close of the weekend you had fallen helplessly in love like a leaf tumbling from a tree.

And then on the Monday morning your first date called your office (these being the days when speaking to people was conditional on knowing where they were, in contrast to today when our voices float in the ether) with an effusive apology and an account of whatever act of minor heroism had kept them from you, but you felt awkward and rang off the call, because while they were out saving lives the world had turned and they had fallen out of it. But they persisted, and eventually you agreed to meet for a drink on Friday after work, as friends, so you could explain how your love life had gone ex-directory. But when you saw the vulnerability in their eyes you remembered why you found them so darned attractive in the first place, and you felt your resolve washing away like sand in the morning rain.

And so you began an affair with the person you’d ditched, behind the back of the one fate had thrust on you in his place, and for a few years you faithfully tended this faithless arrangement, soaking up your friends’ compliments about your successfully manicured life of marital bliss, even as you dipped out of sight to engage in hot urgent sex with your paramour. Until one day your lover died in a car accident, and you gnashed your teeth in silent mourning, and in your secret anguish you accepted your surviving partner’s marriage proposal, believing it would absolve you from your grievous shame. And you lived the rest of your life in a balm of muted happiness tinged with the bitter flavour of regret, as all good marriages are.

Nowadays technological advancement has deprived us of these opportunities. If our dates don’t appear we send them a snarky text message, slip out of the bar, go home and cry in the dark.

Above and beyond

Have two years really gone by, my love? When I think of us together it seems like five minutes ago and another time zone at once, as if I’m watching a live television broadcast from the medieval era.

I look through a telescope in search of you, but all I see is flickering lights. Are they anomalies of bitter heat in the cold, or is the night sky a cloak for the terrible brightness? Is it love distorting the view, or madness? Is there any discernible difference?

There is a school of thought that says that once you’ve taken your last breath and your consciousness fizzles out, it’s as if you never existed.

I have an infinitesimal problem with that.